Boris Johnson, COVID-19 and Oedipus Rex – part 1

The 2,500-year-old tragedy of Oedipus continues to be played out: Boris Johnson’s literal and unimaginative response to COVID-19 has not moved on.

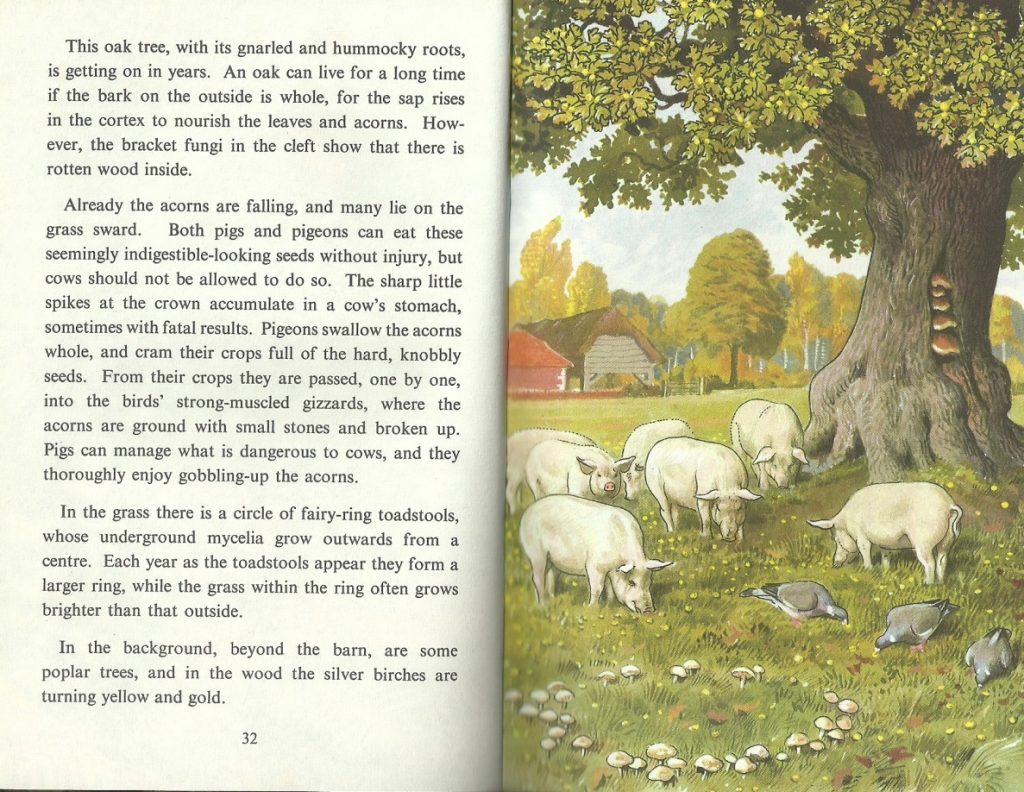

Three years previously I started to write a series of nature posts using the wonderful Ladybird ‘What to look for’ books as inspiration. Other work took over and the project stalled, as things often do. This post marked a temporary return to the series and the last of the Autumn pictures.

My original intent was to reflect on changes in the countryside, to face the losses in the unbearably short time since the books were made. Even since I started writing the circumstances of our lives have worsened. We live in times devoid of leadership, allowing ourselves to be controlled by corporate power and toxic media. In our passivity and delusion, we seem happy to accept the spread of mediocrity and loss of agency. I believe it behoves us all to take back whatever small powers we can, to spread the warning messages far and wide, to say again and again that our blind addiction to wanton consumption is not just unsustainable, but insane.

If you would like to read the earlier Autumn posts, you can find them here:

‘Harvest’: part 1 – naming autumn, a ploughed field, wild harvest, hop pickers, flight of the swallow

‘Fruit’: part 2 – a hayrick, wild berries, hazel coppice, Sydenham Hill Wood

‘Inedible’: part 3 – foxes, fungi, weasels, wild ducks

A digression on shooting pheasants

As I write this in late November, the autumn colours of the English landscape (at their best a week earlier) are disappearing in cold winds. The dynamic mixture of colours reminded me of the dioramas of childhood, where dyed reindeer lichen stood in for trees and shrubs. Now yellow leaves blow along like manic butterflies, the ironic counterpoint of Spring. Frost and ice begin to slow things down – except in city worlds, which know no seasons and barely pause for sleep.

Reflecting on the ridiculous English vs. Spanish bluebell war, Richard Mabey wrote that the Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur) and the Sessile Oak (Quercus petraea) have been regularly hybridising for millennia, yet there is no sign of either original species dying out. There may be specific reasons for this resilience, but the comment serves to highlight the rigidity in some nature conservation.

Native trees and shrubs support a multitude of species and none more so than the Oak (I wrote a separate piece on the extraordinary ancient oak ‘Majesty’ here). Unfortunately, the dance between host, predator and parasite has been rudely interrupted by ignorant human behaviour. Pollution, agricultural nitrates and the traffic in live plants have created massive problems for trees. The virulent form of Dutch Elm Disease that completely altered the English landscape came from imported Canadian logs (the Elm itself is non-native). The fungus that causes Ash dieback also came from imported trees, probably from Asia. Even oaks are now at risk from Acute Oak Decline and Sudden Oak Death.

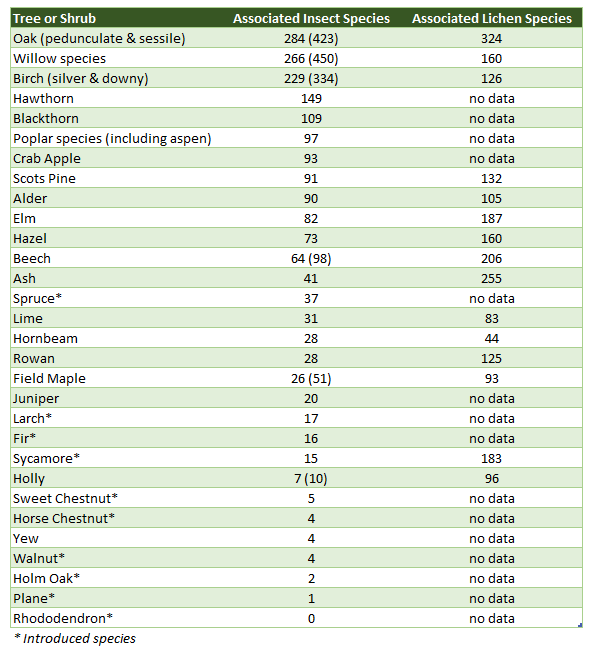

Opinions vary, but oaks support around 300 insect species and a similar number of lichens. Compare this to the sterility of imported species in the table above. Our towns and cities have been largely populated with alien species. In the country, massive conifer plantations, inimical to local wildlife, have effectively depopulated whole tracts of land. All this change has taken place very quickly in the context of historical deforestation.

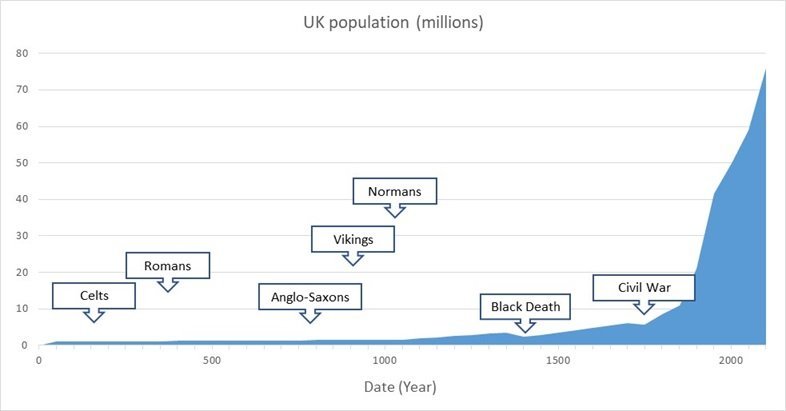

Consider first the population of the UK. Very slow historical population growth suddenly leapt after the enclosures and clearances, and the spasm of the Industrial Revolution.

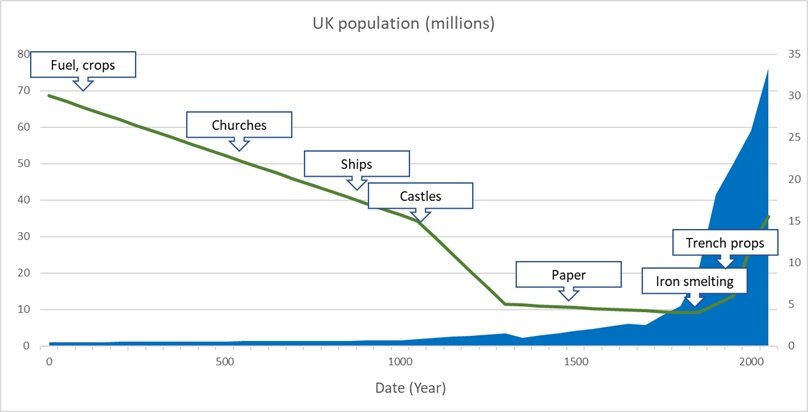

But afforestation in the UK has been low for centuries. Successive needs, starting with fuel and building, and the expense of imported timber meant that forests in the UK suffered more than those in mainland Europe.

Overlaying the population chart with a line for the percentage of UK afforestation shows (as far as one can tell without accurate records) that tree cover reached its nadir in the early nineteenth century and has improved considerably since. However, the improvement includes conifer plantations and many other non-native trees planted for economic and aesthetic reasons. Look again at the table to see that the trees originally native to the UK are also the most important for other wildlife. One-third of the rest of Europe is under forest, so the UK is still lagging behind.

I expected to find that the practice of feeding pigs on acorns would have died out in the UK. To my surprise, I discovered that it is alive in the New Forest with the custom known as the Common of Mast. The New Forest Commons are of Pasture, Fuelwood, Mast and – historically – Marl (lime-rich clay) and Turbary (peat turves for fuel). Sustainable Commons, both physical and figurative, will become more important once again, as the economy begun by the Industrial Revolution convulses.

The ‘Fairy Ring’ of myth and folklore can be caused by a number of species, but probably the most usual is Marasmius oreades, the Fairy Ring Champignon.

With the Eastern Grey Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), which has effectively displaced the native Red Squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) from the UK, we once more encounter the prejudicial word ‘invasive’, a word always used against species introduced by humans that have gone on to prosper. There are few more hypocritical terms than this one.

If our woods were as diverse as once they were, Pine Martens (Martes martes) would quickly bring the Grey population down, to the benefit of the Reds. But Pine Martens are only present in England in tiny numbers, so the spread of the Grey Squirrel goes unchecked. The smaller size of the Red Squirrel apparently gives it the edge over Greys when it comes to avoiding martens. Evidence of this also comes from the reintroduction of the Pine Marten into the Irish Midlands.

The Grey Squirrel also carries parapoxvirus, lethal to Reds. According to the Independent newspaper, parapoxvirus from Greys has all but destroyed a Red population in the Lake District. Grey Squirrels, unlike Reds, strip bark from trees, rendering them vulnerable to fungal attack. Human arrogance is responsible for the spread of the Grey Squirrel, a spread so damaging that the animal is regarded by some as a biological weapon (presumably homo sapiens is the most effective such weapon). The answer lies not with expensive and inefficient culling (or in novelty beer bottle holders) but in increasing diversity. Unfortunately, we are very bad at it. Our monolithic culture pays lip service to diversity while failing to engage with it except in the form of tokenism, or in the conservation of relict populations.

Tunnicliffe’s illustration of the False Death Cap (Amanita citrina) looks a little stylised. Although this mushroom is edible in small quantities, its similarity to other (highly poisonous) Amanita species renders it unappealing. The excellent nature site http://www.first-nature.com, describing the true Deathcap, writes of “the repulsive smell that, to anyone with a nose, should betray the evil within a mature Deathcap”. Such an interesting slip to describe poison as ‘evil’: it could be put to evil use, but in itself is not.

Of the species mentioned in the next image, only the Long-tailed Tit exists in decent numbers. Water companies have substantially reduced the very habitat depicted. Agricultural run-off has poisoned most of the rest. The Kingfisher is on the decline and is on the UK Amber List for birds. Luckily for the Kingfisher, eels are unlikely to be a part of its diet. The European eel (Anguilla anguilla), once a staple food, is now critically endangered. Eels are victims of not only ‘environmental factors’ (code for human habitat destruction), but a roaring trade in eels smuggled to Asia.

The consequence of this shocking greed is that the number of eels in the UK has dropped by a staggering 95% since the 1970s. Eels, as this article makes very clear, have become the ivory of Europe. The image of the stream full of eels was accurate. Rivers, particularly those emptying into the Atlantic, would turn silver with the numbers of migrating eels. This is a sight that is almost certainly lost forever.

The Sargasso Sea, to which mature silver eels travel to spawn and die, has a high concentration of plastic waste. The huge North Atlantic Garbage Patch is there. As we know now, plastic absorbs pollutants, making it poisonous to anything that eats it.

The Tawny Owl is also on the Amber list after declines in population and breeding range. The illustration is prescient. The owl sits aloof, as if in judgment, high above the spectacle of the bonfire. It is a suitable image for our hot ferocious destruction of the world about us.

It is also notable that Tunnicliffe has shown the Scots Pine, the only conifer (other than Yew and Juniper) native to the UK.

If you have enjoyed this article then please consider sending me a donation to help with hosting costs.