Suicide and survival – a personal reflection

The entrance to the Tomb

I’m obliged to wait at the roadside for the 4WDs, trailing behind them their stinking invisible clouds of diesel fumes and privilege. I tell you I’m okay, fix your guilt, ease your dis-ease. To do otherwise would be unkind. Besides, I’m frightened for your fear, knowing that my urge to suicide is its catalyst.

At this moment the successes of a difficult life feel roughly overturned as my flaws, my wounds and my mistakes are used against me to destroy me. Generosity, love and the great things of a life lived are nothing but shameful recollections. The painstaking accretions of acceptability are scoured, racked, blasted; the slowly mortared building of character collapsed in to rubble.

I struggle against the seductive urge to end the pain, and crippling emotional dissonance rides up to smash me with iron hooves. The dire horseman with his bony smile offers blessed oblivion. He is the amber liqueur, the murky opiate, the velvet curtain to darkness. One hard crack and all is softness.

According to the advice site for men with suicidal ideation, mandown, more than 12 men take their lives each and every day in the UK and Republic of Ireland alone. This isn’t a statistic, it’s an epidemic, one unchecked for over twenty years. And now I find myself here again, as one week bleeds soundlessly into the next, teetering on the kerb, watching the blank blonde faces with the tight lips and sunglasses roar past. Their names are:

| Forester | Sequoia | Cherokee | Yukon |

| Outback | Pathfinder | Explorer | Panda |

| Rover | Highlander | Navigator | Kuga |

| Journey | Tundra | Outlander | Yeti |

This piece is my personal guide to staying alive, my Observer’s Book of Suicide, my Collins Gem of Survival. These are the things that keep me going step by step, offered without apology. I cannot offer this piece as self-help, it is personal to me, and I know many will disagree. But I know what things keep me alive, and here I share them in the hope that if just one person reads these words, and can find in them some reason to walk back from the edge, then my struggle will not have been in vain.

I do not look to explain, defend or even contextualise suicidal feelings, but instead to stay with them for a while, and always to honour them. Yes, there is self-pity here, because there is a great difference between pity for the wounded self and weaponised victimhood. For it is clear that whatever we may like to believe about our cultural development, there are people alive who hold any expression of vulnerability in the deepest contempt – most likely because it shines a light on their own suppressed need. This becomes apparent from the most cursory glance at what passes as news, but sometimes an event, such as this one, in which a suicidal man was taunted by onlookers until he jumped to his death, takes one’s breath away. Months after this vile story appeared in the press I am still astonished to read the police statement in which an officer said “We do not condone such behaviour”, as if that needs explanation. The awful truth dawns: perhaps it needed to be said as if there was some doubt.

Abandon hope

There is rarely any respite or care for one in deep limbo, just the day to day doing of staying alive is hard enough. If any of us is to stand up to the passive aggression, pettifogging bureaucratic obstruction and slyly competitive attacks of the inadequate, then we need spirit. Gusto is needed for the skirmish, the extrovert energy that pushes outwards. But depression brings a terrible weariness of the soul, particularly for the introvert. For those on the edge, there is no mechanism, no cognitive apparatus, that can lift one bodily out of the swamp. This is why Hillman was right about hope.1

Hesiod’s tale of Pandora tells us that hope is one of the evils that was in the vessel, and is the only one that remains within. It lies concealed where it is not seen, whereas all the other evils, fancies, passions are the projections we meet outside in the world. These can be recaptured by integrating the projections. But hope is within, bound up with the dynamism of life itself. Where hope is, is life. We can never confront it directly any more than we can seize life, for hope is the urge to live into tomorrow, the heedless leaning ahead into the future. Go, go, go.

James Hillman, Suicide and the Soul, 1965, 1997

The path around the Tomb

So this is the work: abandon hopes and dreams, since those have been squandered anyway. Be alive only to the pains of the moment. Write about them, talk about them, paint them. Rant and froth, vent your spleen, burst your heart. Grieve the loss of hopes and dreams. Let days and nights flood the world with tears until all that is left is the burning heat of anger, as dry and white as the skulls of kine bleached under the desert sun.

Know the age of your anger, whether thirteen or thirty. Celebrate it, shout it to the skies. If your anger is thirteen, there will be a sense of unjustness, the dreadful unfairness of things. If it’s thirty there will be the plunge from the mountain, the sickening fall to the valley floor, the humiliation of defeat. Later, there is weary despair. You may feel all these at once. Trust only your senses. If you are hungry find food. If you are cold find shelter. Don’t hope for charity, don’t feed guilt. Walk, if you can, like Kipling’s cat through the Wet Wild Wood. If you have nothing else, let anger heat you and feed you.

When you trip, that’s the earth calling to you out of your fantasies, flattening you and grounding you. Sudden grounding needs quiet for sitting, a drink of water and peppery greens so fresh they squeak as you chew. Do no harm to others, their failure is not yours. Love them for what they could be, not what they are. Appreciate their anxiety for you, their need for you to survive. Try to listen to their hidden anger with you, but do not be swayed by it, the answers lie elsewhere.

Hillman quotes Eliot:

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets – East Coker, 1940

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love,

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

He might also have added the next two lines:

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

T. S. Eliot, ibid.

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

Hope is seductive, it whispers sweet nothings in our ears, coils itself around our bodies, probes for soft spots, fills us with sweet yearning. The present, when we crash back into it, becomes all the more unbearable. By making a conscious effort to abandon all the painful hope, the misdirected love and the contorted thinking, then, at last, we can be present to death and what it wants of us. To be present to death is to accept it but not to embrace it. If you survive, and I hope you do, then there will be a time for hope again.

Care of the Soul

Just about every other psychotherapist’s website will bore you with the information that ‘psychotherapy’ is composed of the words Psyche and Therapy (which mean, roughly, ‘care of the soul’) and that the word ‘therapy’ comes from the Greek word therapeia (θεραπεία) meaning ‘service, attendance, healing’.

The word therapon (θεράπων) means ‘servant, a person who renders service’, but there is an older meaning too, that of an attendant at the altar, one who perhaps kept the torches lit, swept up the ashes of burnt offerings and kept counsel with the gods and the dead. This other meaning places therapy in the context of ritual and takes it out of the orbits of the medical (therapy as talking cure) and the economic (therapy as management).

Nowadays the rituals we observe in the West are little more than those of birth, death and marriage, and even those have lost their importance. The depressed and suicidal need their own rituals, to be able to disappear for a while, free of obligations and responsibilities to family, friends and state. To be able to visit the Underworld but to be free to return. I only know of one organisation in Britain, Maytree, that offers this invaluable service – an oasis in which to be with yourself, and only to talk if you want to.

It is immeasurably useful for us to be able to spend time in the swamp, to be still in the viscous liquid and noxious vapour of our despair. In our culture this is denied, and if we venture in we are held to be self-centred and self-regarding. This is wrong, and a function of the fear and need of others. We need to acknowledge that there is danger in the swamp, that for some of us the pull of the Underworld becomes irresistible. The other Greek name for the Underworld (other than Hades) is Pluto, a name also synonymous with riches (e.g. plutocrat). Gold and diamonds come from underground, seeds lie dormant in the earth, treasure is buried. There is a pull that relates to something other than death as the mere absence of life.

James Hollis writes:

The good news deriving from our confrontation with death is that our choices really do matter and that our dignity and depth derive precisely from what Heidegger called “the Being-toward-Death.” Heidegger’s definition of our ontological condition is not morbid but rather a recognition of the teleological purposes of nature, the birth-death dialectic.

James Hollis, The Middle Passage, 1993

In clearer language, let us be up to our noses in the foul swamp, fully tasting the bitterness and the disgust, just so long as we have enough space between the putrid liquid and our nostrils to breathe. This honours the confrontation with death rather than repressing it, and it allows a choice because life and death need to be choices. Any other way is to surrender to the monolithic thinking of state and culture that has driven many of us here to begin with.

How therapy might help

Good therapy is difficult to define. What works for you might be anathema to me. Many (if not most) therapists are rescuers. If the rescuing tendency is conscious the therapist will avoid it, but it runs deep in the psyche and compromises the therapist’s capacity to sit with suicidal feelings. Worst of all can be the normalisation that some therapy seeks to create. Therapists are taught this, to make distress acceptable, to explain that what you’re feeling is ok. This is designed to help you feel better about your distress, to understand that your response fits into the spectra of typical emotional response, and it places those feelings in the context of society at large. But this ‘flattening’ can become insidious, threatening to corral and correct the extraordinary, to legitimise and normalise not just our pain, but its causes. At its worst, therapeutic normalisation leads to the grey goo of mediocrity, it dishonours feeling, it nannies and coddles death itself.

The widespread adoption of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy means that anything felt instinctively is often viewed as primitive, of less ‘value’ than rational thought, and this reinforces the split between Logos and Eros. Our society has become almost entirely Apollonian, possessed of structure and reason, whereas the Dionysian, being properly the felt sense of belonging fully to nature and the wild, has become the heedless affirmation of life, ‘go, go’ go’, constant running. These two have become split, opposites, but long ago they were half brothers, two sides of the same coin. In popular culture we can think of the Spock/Kirk pairing in Star Trek. These two respect each other: they are separate (Captain Kirk/Mr Spock) but in crisis they are intimate, they are Spock/Jim.

A therapist should be able to hold a space, so even if your therapist cannot meet your despair on equal terms, if she or he has a decent room, a place of peace, use the hour to listen closely to your body. When I can do this for myself I can feel the ache in my shoulders I wasn’t even aware of, the ache that comes from bunching up my shoulders to withstand a blow, and from carrying a heavy load. I can reflect on the unequal metronome of my heart and the shame of my churning gut; I notice how the muscles of my thighs are tense from the need to spring into fight or flight.

Find your own tell-tale signs, the messages with which your body informs you of its distress. Perhaps a foot that waggles autonomously, a death-watch of suppressed fury; maybe the deep sucking sigh of grief or the persistent patch of eczema that you scratch at when you are under the spotlight. Observe but suspend judgement, no matter how shameful the feeling. Your symptoms are unconscious protests made visible in the body. Find the image, for the image speaks to the soul. Your wagging foot might be a factory machine, always in motion, required to produce endlessly; your sigh a sea-bell, echoing in the confused fog of loss. Your scratching, the frantic scrabble of a rat, desperate to escape a flooded oubliette. Let your imagination emerge from its place of hiding.

Deflation

I mentioned extrovert energy. This is the thrusting, penetrative, exploratory ‘cock energy’ that I wrote about in a previous piece, it is the energy of the improbably endowed Priapus, a son of Aphrodite and Dionysus, his enormous dick the consequence of vengeful Hera’s curse. This energy is neither male nor female but is more often associated with men. What happens when this energy is reduced, when one feels flaccid, impotent? I think that shame appears, the fear that others will see our impotence, judge it, mock it. In men, the shame might be felt in the scorn of women or the contempt of other men. Look at me, I can’t get it up in the world, I can’t make it, I can’t take the decisive actions or make the bold choices that signal life, I can’t even fake the behaviour that is now worshipped in our culture.

In the picture, we see Priapus weighing his improbable member against a bag of money, the worth perhaps of the fruit below. The painting is in the Casa dei Vettii in Pompeii, where it is positioned immediately inside the front door. Priapus was apotropaic, he had the power to avert bad luck or the evil eye, and the painting, aside from elements of the comic2 and the threatening, suggests that while Priapus’ virility does not outweigh material wealth3 neither is it the lesser of the two. Priapus’ erection is pointing to the basket of fruit: it is as if his explicit energy is showing us its root in fertility. There are grapes there, that belong to Priapus’ father Dionysus (Bacchus to the Romans) and a pomegranate, the three seeds of which bound Persephone to Hades in the barren months. The message seems to be that natural wealth, illustrated by the fruit, is the foundation without which business and its proceeds cannot exist – that the true value of life lies in the abundance of nature.

To go swimming spontaneously, without consulting the oracle of tide tables, is to risk disappointment. If the tide is too far in, there may not be a place to camp on the beach. Too far out and there might be a long walk to the sea. But both states offer something else. At high tide, I can sit with the waves, admire the sweep of the vast sea. At low tide all the pools and rocks are exposed, plants and animals are now rendered vulnerable to observation and predation. So with our souls in crisis.

Am I overwhelmed by high tide, the energy of other people? Am I deflated by low tide, do I feel as if I’ve failed? Or can I acknowledge that there are riches to be found in both states? At high tide, I have a panoramic view and I feel expansive, the captain of my ship. At low tide, I hunker down to poke around in the weed and under the slippery rocks of the psyche. And as much as I might first be repelled by rank encrustations and the pale worms that ooze through the substrate, I might also allow myself to imagine those beings when they are once more immersed in the sea, to recognise that an organism is the same regardless of it being in or out of the water.

Priapus is also a god of the garden, of flowers and bees (think of a bee penetrating a flower), and of vegetables (I imagine gourds, squashes and beans). I think of the phallic force of plants pushing up through the earth, the coiled and secret intention of bulbs and seeds, brought to life by heat, light and water. So I too might one day push up from the subterranean depths (the father: Dionysus) into the light (the mother: Aphrodite). These are not places in opposition (like Hell and Heaven) but necessary parts of the whole. The earth engulfs the tomb, it freezes the seed, it is hard, but it also holds and protects. The light brings visibility and risk, but also warmth and love. Few have so understood the erotic energy of growth (and its intimate connection to death) better than the nineteen-year-old Dylan Thomas:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.The force that drives the water through the rocks

Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams

Turns mine to wax.

And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins

How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks.The hand that whirls the water in the pool

Stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind

Hauls my shroud sail.

And I am dumb to tell the hanging man

How of my clay is made the hangman’s lime.The lips of time leech to the fountain head;

Love drips and gathers, but the fallen blood

Shall calm her sores.

And I am dumb to tell a weather’s wind

How time has ticked a heaven round the stars.And I am dumb to tell the lover’s tomb

Dylan Thomas, The Poems of Dylan Thomas, 1934

How at my sheet goes the same crooked worm.

How ideology moves against the soul

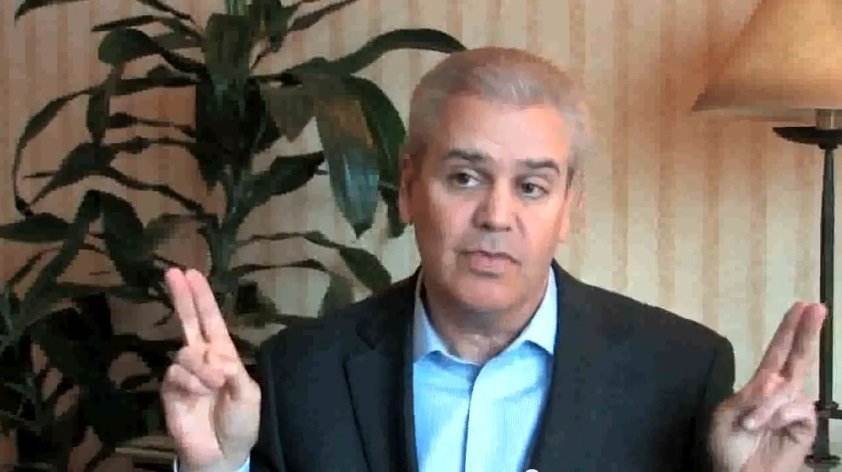

Some time ago I received an email from n-science for one of their future events, a talk with Dr Eoin Galavan on ‘The Assessment and Treatment of Suicidality’. I have not met Dr Galavan, I know nothing of him. He looks like a nice warm chap and I’m sure he is. He is also the ‘CAMS representative in Ireland, licensed to research the CAMS model, a consultant with CAMS-care’. What then is CAMS? It is ‘Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality’, a method of treating ‘suicidality’ devised by Professor David E. Jobes, who is Professor of Psychology at The Catholic University of America and a self-described ‘career suicidologist’. Alarm bells start to ring. The Catholic University of America says this of itself:

As the national university of the Catholic Church in the United States, founded and sponsored by the bishops of the country with the approval of the Holy See, The Catholic University of America is committed to being a comprehensive Catholic and American institution of higher learning, faithful to the teachings of Jesus Christ as handed on by the Church. Dedicated to advancing the dialogue between faith and reason, The Catholic University of America seeks to discover and impart the truth through excellence in teaching and research, all in service to the Church, the nation and the world.

Mission Statement, Catholic University of America

CAMS-care, with its e-learning and licensing, is a business. A business that is built around preventing suicide on implicit and unstated ideological grounds. At first glance, the underlying philosophy seems to be a move towards soul (all that follows can be found here (PDF):

Suicidal thinking and behaviors are often a perfectly sensible – albeit worrisome and often troubling – response to intense psychological pain and suffering. In a similar sense, I would contend that all suicidal persons have struggles that are rooted in legitimate needs and concerns. For example, most suicidal people feel they simply cannot bear the pain they are in and they understandably seek an escape from their suffering. Others desperately want their loved ones to know how much they suffer or feel compelled to unburden those who love them. Still other patients, in acute psychiatric distress, may feel compelled to perform acts of self harm as a capitulation to punitive voices they hear within a psychotic state.

The CAMS Approach to Suicide Risk: Philosophy and Clinical Procedures, David A. Jobes, 2009

But this is hardly an inclusive understanding of suicidal thought, and barely an adequate summary. It ignores (for example) suicide as revenge, suicide as aggression, or suicide as blackmail. Let’s move on to the clinical example given by Professor Jobes:

Patient: I suffer so much and no one seems to care; my husband just ignores me – he gets mad at me and tells me to get over it, snap out of it!

Clinician: You feel like no one appreciates your struggles, particularly the person want you most want to care?[sic]

Patient: It’s not just him, it’s everybody – my parents, my kids, and my so called friends… you know I honestly think sometimes they would all be better off without me…

Clinician: It sounds like you feel that you have become a burden to them? Does this view of things ever lead you to thoughts of suicide?

Patient: Well yes, I have actually thought about suicide quite a bit lately.

Clinician: I see… and when you think about suicide does it upset you or comfort you? Does it frighten you? Or instead, does it give you a feeling of control and power over your suffering?

Patient: It is more the latter because it does make me feel like there is at least one thing I can do about this whole wretched situation that I am in… I just can’t bear the pain… it’s all too much for me…

Clinician: I see… well let’s be frank… of course suicide is an option that many people use to cope with these exact feelings. And yet if it was the best thing to do, it seems unlikely that you would be here with me in a mental health care setting, right? From my bias, while I acknowledge the option of suicide for some people, I would like to see if we could find a way to end your pain, and get your needs met, without you needing to take your life. In my mind, you have everything to gain and really nothing to lose by earnestly trying to engage in a life-saving treatment. There is a treatment I would like to try with you called “CAMS” – it is designed to help you learn to cope differently and better and it could help you get your needs met without having to rely on suicide. To this end, I wonder if I could persuade you – if you would consider – engaging for 3 months in this suicide-focused treatment… I really think it could be quite helpful to you.

Patient: Well that is asking a lot… I really don’t know if I am up for doing something like that…

Clinician: Yes, I understand; but then again you have everything to gain and really nothing to lose. While it is not my preferred means of coping, you always have the prospect of suicide to fall back on later when you are not engaged in a life saving clinical treatment. But for now, I would like to see if we could find a way to make this life more worth living through this approach. Given the life and death consequences, I do not think it is too much to ask of you to give this CAMS approach a go for three months… what do you say?

Patient: I guess we can try, maybe it can help? But you are right, the reason I am here is that I am just not yet ready to exercise my suicide option… How exactly do we do this CAMS?

The CAMS Approach to Suicide Risk: Philosophy and Clinical Procedures, David A. Jobes, 2009

I squirmed around reading this, deeply discomfited by the way the feelings of the imaginary patient are acknowledged yet she is still led by the nose. Mental health care in the US, and in many other countries, is fraught with fear of litigation. Jobes himself, in this YouTube video, talks of the fear of the mental health ‘provider’ faced with a suicidal patient: first anxiety over competency, and second the fear of litigation. The question of the patient’s anxiety and despair is not even mentioned.

Out of this fear, Professor Jobes direct method of engaging with suicidal feelings seems to make sense, but his ‘paradigm shift’, his model of empathy, is something that the ‘provider’ should be engaged in from the outset. Jobes complains of the movie representation of ‘providers’ as crazier than the patient. Of course we are, or should be, and keeping our wounds open for the benefit of others. How can therapists relate authentically to anyone unless just mad enough to make the leap themselves into the Mundus imaginalis of self-harm, suicide and madness?

Therapy as a control mechanism

Jobes speaks of needing to get ‘family members and loved ones’ involved with his ‘intake’ of the ‘middle-aged, white male, who’s got insomnia and an alcohol problem and is a gun owner, and has a history of major depressive disorder and anxiety and agitation, and has a poor history of treatment compliance‘ (my italics) because (and here come his hands, up in the air making quote marks, like Jesus Christ spelling his name on a Byzantine icon) he might incur ‘some measure of liability’. So motivation on the part of the suicidal patient is deemed to be important. Professor Jobes doesn’t want to work with you otherwise. He loves his intervention though, he finds it ’empowering and honest’ to tell people that he won’t work with them if they’re too difficult for his pragmatic approach. He says, explicitly, “I think I’ve got certain gifts, but suicidal patients in my early career terrified me, they still do, it’s very anxiety-provoking.”. To manage his anxiety he is “gaining mastery… I need to practise from a sense of confidence and competence.” I can’t imagine a worse place to come from. Jobes ends his video with some self-serving blather about the ‘taskforce’ being at the ‘cutting edge’, and, messianically, he says his method is “indexed to political realities, to health care reform and to mindfulness… cost-effective treatments, evidence-based treatments, I think it’s a new horizon, a new world…”

This is the tool:

The full Suicide Status Form (SSF, seven pages) provides a means for:

- Initial assessment and documentation of suicidal risk

- Initial development and documentation of a suicide-specific treatment plan

- Tracking and documentation of on-going suicidal risk assessment and up-dates of the treatment plan

- Ultimate accounting and documentation of clinical outcomes.

Checkboxes are ticked, boxes filled, dates given, and signatures appended (the three words that each stage have in common are ‘and documentation of’). At the end of the three months that the intervention takes, the final step is reached:

Three consecutive sessions of no suicidal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors marks the resolution on suicide risk; the SSF Suicide Tracking Outcome Forms are completed and the patient is taken off Suicide Status as CAMS comes to a close.

The CAMS Approach to Suicide Risk: Philosophy and Clinical Procedures, David A. Jobes, 2009

Professor Jobes and his licensed clinicians have saved lives, their forms prove it. They have worked exclusively with motivated patients, they have delivered their interventions competently and confidently, and they have expertly managed their liability. There is more material featuring this nauseating man, but after a few minutes of his address to a conference I felt too sickened to continue.

Why do I care? Because this is over here, promoted without any exploration of the ideology behind it: the underlying belief that suicide is a sin. It is another move away from soul, utterly devoid of any attempt to meet, on their own terms, the figures of anxiety, futility, meaning and love. It is the grey, risk-free, joyless and narcissistic management of profound despair, delivered only to the compliant.

Work, Shame and the Charm of Making

It matters little if you are working or not, the febrile energy of other people will simultaneously repel and shame you in your cold orbit. Your task is to recognise it, that’s all. The polis4 fears and defends itself against the outsider. It seeks to absorb you because the depth of your feeling shines a baleful light on the unreality of most modern work. Much as I reject a group I feel the separation from it, the almost visible stigma, as a great gaping maw of humiliation. I need to connect, but not at any cost.

Work requires connection and soul just as much as any other activity, perhaps more so because of the central part it plays in our lives. But most work today is tyrannical, it makes us fearful slaves.

I recall the weekends and evenings in which I would hide from my family at the top of the house, building and painting models. As I grew more skilled I would modify and adapt, raising lines of tiny rivets with polystyrene sheet and an old biro, creating whip aerials from scrap plastic slightly melted with a candle. I would paint a delicate scar on to the cheek of a miniature tank commander; highlight the lantern jaw of a cuirassier; pick out the piping on a hussar’s jacket. As I looked into the tiny eyes of my soldiers I saw myself reflected back. The most minute movement of the brush tip would change a face forever: a louche Gauleiter would mysteriously achieve some strange nobility and, Janus-like, the profile of a Napoleonic dragoon might first suggest sadness, but have a sadistic leer impressed on the turned cheek.

Needless to say, my father held this exacting work in contempt. The only praise I recall from him was when I once built a wooden fishing boat from scratch. I understand why: he had no father himself, no man to praise his creativity, but I don’t forgive his cowardice. That is what it is when we feel so angry and bitter with our own childhood life that we are unable to praise the modest achievements of our children.

The Charm of Making5 saved me from some of the toxicity of my family.

The Genius of Place

Surely the best thing to do would be to build one’s own home, perhaps a cob house, to source and prepare each material, to feel the deep satisfaction of each completed action, the patience needed with the weather. But to do this requires land, resource and time. One thinks of Winston Churchill building brick walls as a bulwark against his depression and the kind of cottage he fondly imagined that working-class people inhabited. C. G. Jung built his ‘tower’ at Bollingen. Of course, Jung had the luxury of his wife Emma Rauschenbach Jung’s inheritance, but he added to his tower over the years, and lived in it without electricity for months at a time, fetching water and chopping wood. The cube Jung fashioned in 1950, and set on the shore of Lake Zurich, has this inscription on one of the faces:

Time is a child — playing like a child — playing a board game — the kingdom of the child. This is Telesphoros, who roams through the dark regions of this cosmos and glows like a star out of the depths. He points the way to the gates of the sun and to the land of dreams

The image inside the inscription is of Telesphoros, in Greek mythology a son of Asclepius the healer, his name means ‘the completing’ or ‘the accomplisher’. Curiously, this minor god could be Celtic in origin, a Genius Cucullatus (hooded spirit of place).

The figure of Telesphoros was that of a cowled dwarf or a boy and was revered as such, but inside the outer boy was a hidden creative god in the shape of a phallus. The Roman’s regarded the phallus as a symbol of:

[…] a man’s secret ‘genius’, the source of his physical and mental creative power, the dispenser of all his inspired or brilliant ideas and of his buoyant joy in life.

Marie-Louise von Franz, C. G. Jung, his myth in our time, 1975

Jung’s purpose in carving the image on the cube was to honour his childhood dream of a ritual phallus, the dream that had signalled his path towards psychology, the land of dreams.

Telesphoros, whether of Celtic or Greco-Roman origin, signified the mystery of sexual union and inner transformation, and the cult of both figures was widespread. This makes me think that men should begin to see their cocks in a different way. Jung explained that sometimes the soul sometimes asks us to die figuratively, to alter our consciousness in response to new self-knowledge, but we literalise this death with tragic consequences.

Whether it is an issue of honour, loneliness, defiance or despair, the sense of an unredeemable past or a future that offers no possibility, suicide often represents a flooding in the psyche of obliterating force. Passive as well as active, suicide may harbour within its violence the desire for transformation, or may signify an evasion of it.”

ARAS, The Book of Symbols

Hillman added:

[…] more could be said about the literalism of suicide – for the danger lies not in the death fantasy but in its literalism. So suicidal literalism might be reversed to mean: literalism is suicidal.

James Hillman, Suicide and the soul, 1965, 1997

In this culture, a man’s cock is literalised as his potency in the world, the bigger the better, so as to be hard and thrusting. Terabytes of pornography reinforce this message. What if we learned something from this ancient tradition of either the ‘hooded spirit of place’, or the ‘accomplisher’, a boy who contains the spirit of transformation, who embodies ‘his buoyant joy in life’?

Suicide and the Garden of the World

Perhaps the real subtext of Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers was the rise of Logos and the pathological fear of the feminine. In the final scenes, we see Donald Sutherland’s character at work, cutting press clippings just as he does in the opening scene. We feel uncertain, has he been absorbed or not? Only the hideous scream with which he betrays the last human (a woman of course) reveals the truth we fear to admit. So seek out the human, the living, the feminine wherever you can find it, remembering that the feminine is not always to be found in women. It is a principle, an energy, that holds and nurtures, and it needs your masculine energy, your holy desert fire, for the dance of life. The reverse may apply, your feminine may be too enveloping, too demanding.

Witness another’s distress but don’t feel that you need to do anything more, at least not yet. In itself, the act of witnessing is a profoundly important and political act. It belongs to the communal, to Alfred Adler’s vision of gemeinschaftsgefühl (community feeling), a felt connection with both the human and the other-than-human, a connection described as sub specie aeternitatis to indicate that it is envisioned from an eternal perspective, not the grim monolithic deceit that can masquerade as reality.

Yet through depression we enter depths and in depths find soul. Depression is essential to the tragic sense of life. It moistens the dry soul, and dries the wet. It brings refuge, limitation, focus, gravity, weight, and humble powerlessness. It reminds of death. The true revolution begins in the individual who can be true to his or her depression. Neither jerking oneself out of it, caught in cycles of hope and despair, nor suffering it through till it turns, nor theologizing it – but discovering the consciousness and depth it wants. So begins the revolution on behalf of soul.

James Hillman, Re-visioning Psychology, 1976

Why all these pictures from nature? I took these on Barnes Common and Leg o’Mutton pond in London as I stood on the edge of things last year. I spent time with these plants and flowers, as I did with the birds and early insects around them. They anchored me and kept me here, and sometimes I would pass someone else to nod to, an acknowledgement of some shared aim – a woman with her face held back in the sun, smiling; two boys with a camera, busy with a school project; a man hunkered down by the water’s edge, apparently in an intimate discussion with a pair of swans.

Dionysus walked here with me (arm in arm with Apollo), sometimes in rapture, sometimes in tearing black despair. Apollo offered thought, smoothed the jagged edges, got me home alive. With Dionysus, I had these moments of bliss: the scent of wild cherry, that I always fancy smells of oxygen; three mistle thrushes churring in a tree; the call of a solitary chiffchaff, the first of the summer. And all the while, as I thought and felt, I noticed the consciousness about me, not the deathly collective consciousness of the culture that condemns the suicidal for being ‘selfish’, for ‘wanting to take the easy way out’ (as it barrels down the road consuming every resource in its path), but the consciousness of the living.

In those moments (as a greenfinch darted across the path or as a heron flapped lazily up to its nest) I talked partly with Apollo, agreeing to relinquish my role as knight paladin and healer, the role that I thought would save me. With Dionysus, I acknowledged my pain, torment, and anger – but also the extraordinary beauty around me. As for my own voice, I remembered the warmth of skin, the light that glitters on the sea, the sigh of wind in the blackthorn, and the taste of being loved. Some self-pity, some yearning, but mostly gratitude, not hope.

If you go for a walk, remember that a place is not obliged to give you anything, you have to ask, and even then you may be disappointed. Just question how you came to that place and what you were expecting.

In another universe, and perhaps in our own future, there will be community areas with ritual spaces: fire pits, steam galleries and quiet wild gardens to sit in and to walk around as we talk, rage and cry together. Valued hetaerae of every gender and orientation will administer sexual healing and we will take coffee at the imaginarium. Until that day, in this grey individualist world of competition, contempt and literalism we must cultivate our love, for love transforms.

While I wrote this piece dreamed one night of Anna, the young woman I worked with who took her life on New Year`s Eve. I woke begging her aloud to come back, my pillow wet with tears. It is for this reason too that I hesitate at the kerb because I would not wish that anguish on another.

Natural, reckless, correct skill;

Ikkyū Sōjun, 1394–1481

Yesterday’s clarity is today’s stupidity

The universe has dark and light, entrust oneself to change

One time, shade the eyes and gaze afar at the road of heaven.