Boris Johnson, COVID-19 and Oedipus Rex – part 1

The 2,500-year-old tragedy of Oedipus continues to be played out: Boris Johnson’s literal and unimaginative response to COVID-19 has not moved on.

The dreadful sound of shuffling feet, and the hideous rattling groans, announce the arrival of the cultural phenomenon of zombie films and games, rich hunting grounds for psychological discovery. In this piece, with my crossbow to hand, I attempt to explore some of the possible figurative responses to the epidemic of zombies in Western culture.

To deprive a gregarious creature of companionship is to maim it, to outrage its nature. The prisoner and the cenobite are aware that the herd exists beyond their exile; they are an aspect of it. But when the herd no longer exists, there is, for the herd creature, no longer entity, a part of no whole; a freak without a place. If he cannot hold on to his reason, then he is lost indeed; most utterly, most fearfully lost, so that he becomes no more than the twitch in the limb of a corpse.

John Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids

At the simplest level, the zombie infestation of popular media deals with two main implicit themes, dissociation and consumerism.

Humans are a gregarious species that came together because it was easier and safer to hunt and live as a group. By so doing, we began to lose our freedom and wildness. The body psychotherapist Nick Totton called this the neolithic bargain. In dissociative behaviour, we witness the loss of this group connection. We lose the small signs of acceptance that bind us together, our language, our desire, our compassion. The consumerist theme is political, it is a reflection on the plague of mindless consumers that is a response to late capitalism (witness the UK rioting of 2011). Watching media coverage of looting, legal or otherwise, we are reminded of zombie attacks. “Look at them, they’re not human,” we say, watching the flat-screen TV that we have looted more respectably.

By iterating the principle features of zombie-related films and games, as represented in this instance by the first three seasons of AMC’s enormously popular television series The Walking Dead, other aspects appear. But first a warning: if you have any intention of watching the series you might want to stop now: there are spoilers ahead!

Let’s look at these features in the light of contemporary events.

It is clear that life, as experienced by current adult generations, has changed dramatically in the last seventy years. This change is mostly a consequence of the development of computing power. In the last thirty years, there has also been a shift towards what is described as neoliberalism. This means deregulation of markets, an increase in privatisation and a reduction in government oversight. These changes have effectively polarised global cultures.

C. G. Jung developed Heraclitus’ concept of enantiodromia (literally, counter running) to explain the tendency in us to manifest the undesirable ‘shadow’ aspects of our parents. So out of a desire for peace and equality comes a surge of aggression, inequality and slavery. The American therapist Cliff Bostock described the physical loss of voice that attended his attempt to lecture from an entrenched position, signalling an urgent need to recognise the compensatory opposite.

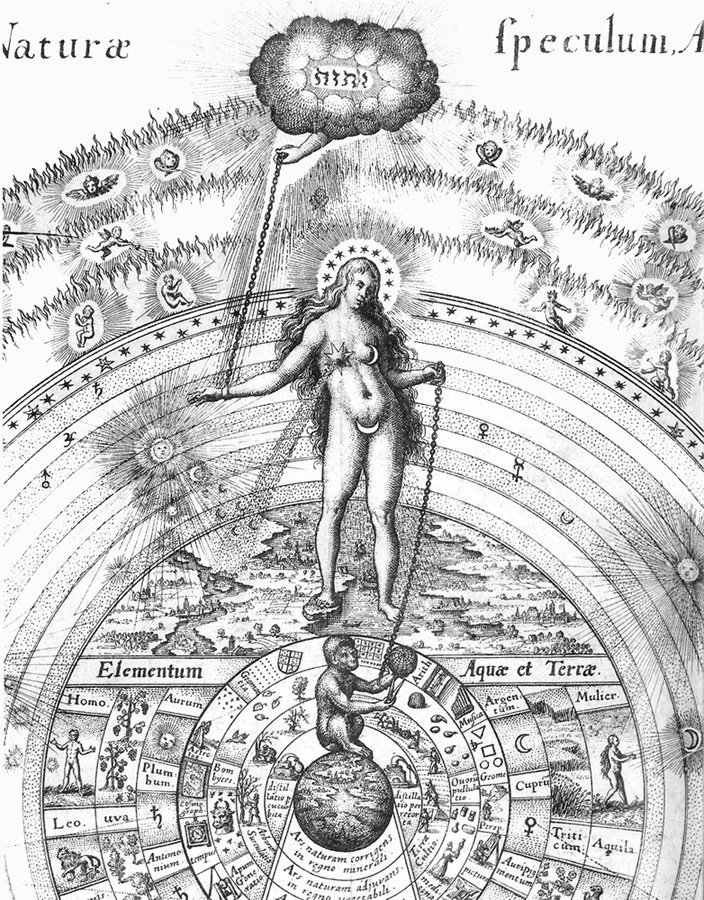

Bostock referenced James Hillman, as do I in these pages, because Hillman recognised that the path we are on excludes the anima mundi, the soul of the world. Hillman argued that psychotherapy has protected sensitive adults from taking action in the world, that their fears and fantasies have become ‘managed’ rather than given expression through action and protest. Moreover, dissent is now effectively psychopathologised and ‘education’ teaches compliance (more on this at a later date).

In the absence of care for the outer world, it has become toxic with crisis. There is financial crisis, economic crisis, crisis in education, housing crisis, fuel crisis and environmental crisis. Myopically, we have climate ‘change’. Small wonder then that the rapacious, tyrannical power of the few has created a world that feels broken and desperate, and that existence has become precarious. In the West, this is the world of the Food Bank, the last resort before begging. It is close to the anarchy of doing a ‘run’ to the abandoned convenience store for supplies. Much as survivors risk the bite of the zombie, the impoverished urban dweller will dash to the supermarket, ever wary of the bailiff.

It must be, I thought, one of the race’s most persistent and comforting hallucinations to trust that “it can’t happen here” — that one’s own time and place is beyond cataclysm.

John Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids

And what of our minds? The psychiatrists’ bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) describes lived experience as disorder. The volume has generated much criticism: first, ‘disorders’ are not diseases as this article makes clear; second (as this piece explains) the ‘treatment of’ so-called disorders makes money. The sale of antipsychotic drugs alone is worth billions. Telling isn’t it?

The opposite of ‘Disorder’ is ‘Order’ but, as Bostock points out, trying to create balance opens the door to chaos. On the churning sea, desperate to survive, we run to one end of the lifeboat to prevent it capsizing. In doing so we start an opposite disaster. We run to the middle, but balance is too difficult to achieve, we never seem to get it right. Perhaps only by dancing between the peaks and trouighs can we keep from capsizing.

Our ‘dis-orders’ and ‘dis-eases’ are also symptomatic of the toxicity prevailing in the culture. We project blame onto those of us who are merely displaying the symptoms of the true malaise. This leads to a further paucity of imagination and monolithic, monomaniac behaviour.

In my work as a therapist, I saw a rising incidence of difficulty with anger, anxiety and ‘depression’. Many visitors were in denial of those feelings. Peopled believe that they choose their mechanical lifestyles – or else that there are no options. This is the absence of imagination again. But it is not of the trapped individual so much as the larger society. There is a terrible cost. Anxiety and depression are medicated, anger is managed. Zombies only want living flesh, they are driven to it, they have no options, not even binary options.

It has been almost 50 years since Elisabeth Kübler-Ross developed her five stages of grieving. She worked with people dying of a terminal illness rather than the bereaved. Subsequent researchers have taken a more expansive view of grieving. Others have denied the five stages entirely, preferring a model of stoic resilience, and setting these two states in opposition. In this piece, the psychiatrist Steven Schlozman writes of the trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in The Walking Dead. He writes that the phenotype is different between characters, but his examples strike me as rather literal. And here it is argued that the series is a critique of individualism. But I see the tendency of troubled characters to go out alone as a dramatic staple of the horror genre (no, don’t go down into the cellar with just a candle and a scared look!).

Nick Totton references the anthropologist Richard Sorenson:

[His] work suggests that once dominator culture arises it spreads like a plague: cooperative, liminal, wild humans are profoundly vulnerable to humans who are closed and aggressive. They literally cannot bear to be around them.

Nick Totton, Wild Therapy, 2011

Another pair of opposites perhaps, but one that is well illustrated by the competing camps of The Walking Dead. There is one notable difference: the cooperative humans are prevented from being in the wild. How similar to current society. There are so few ways to escape from the dominator culture, and it is this that we desperately need.

If I am right in my opinion about the prevalence of anxiety, depression and anger in Western culture, we can relate these symptoms to the oppression of the dominator class. We can also connect them to loss. So what might be lost? According to Jay Griffiths in her book Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape the loss is environmental. She writes that since the enclosures, peasants were funnelled into industry away from the land. The idea that this rescued a brutish rural population from the miseries of subsistence farming is a myth created by landowners and industrialists. Griffiths too sometimes inhabits the land of opposites. She compares the evils of the modern world to an Arcadian fantasy. But her Romantic passion lights up the heart. One wants to be in the cool streams and secret dens of her imagination.

Ecopsychologists suggest that we are all grieving for the other than human, the countless species and the sheer numbers lost. We face the sixth extinction, a wiping out of life on a massive scale. Impossible? Remember the fate of the Passenger Pigeon? Billions of birds were made extinct in 40 years through hunting and deforestation. More recently, the Pyrenean Ibex: extinct in 2000. The Saint Helena olive: extinct in 2003. The Bramble Cay melomys: extinct in 2016. And not just species, but unimaginable numbers of individuals wiped out through human agency. Now scientists are talking of ‘de-extinction’, of reanimating these species from their DNA.

I think that we carry the knowledge of what we have done as a terrible shame. The zombie herds of The Walking Dead reflect our continuing predations on the natural world. They push their way through everything in their need for the flesh of the living, just as we bulldoze our way through the Earth in our need for its resources.

In the first two series of the Walking Dead, the farms and lush countryside of Georgia shimmer in the heat of high Summer. Sweat drips sadly from the noses of protagonists. Winter is mentioned but avoided, and soon we are back in a verdant Spring – but here there is still danger. Behind every tree, a zombie may lurk. Down at the stream zombies are stuck in the mud. A child’s den is a place to hide in terror from the awful groaning outside.

In the third season, the irony is signposted in block capitals. Our heroes set up home in a bleak grey prison that has to be regularly cleared of the undead. Outside, zombies congregate at the prison fences, groping for a way through. The group struggles between the ‘freedom’ of the prison and the ‘safety’ of a ‘community’ run autocratically by the ‘Governor’. To what extent do these set pieces reflect our lives? Here we are in opposites again. The fearful grey fortresses of the heart stand in for Independence, while the phoney veneer of the Governor’s colony is Dependence. Neither option is attractive and the ground between them, the beautiful forest, is rendered toxic and uninhabitable.

John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids is the prototype here in so many ways, from the hospitalised hero waking to a world turned insane, to the competing camps of survivors. But instead of what Brian Aldiss described as ‘cosy catastrophe’ (the barely conscious wish for the slate to be wiped clean so that we might create Arcadia) there is next to no comfort, or the comfort is soon violently removed.

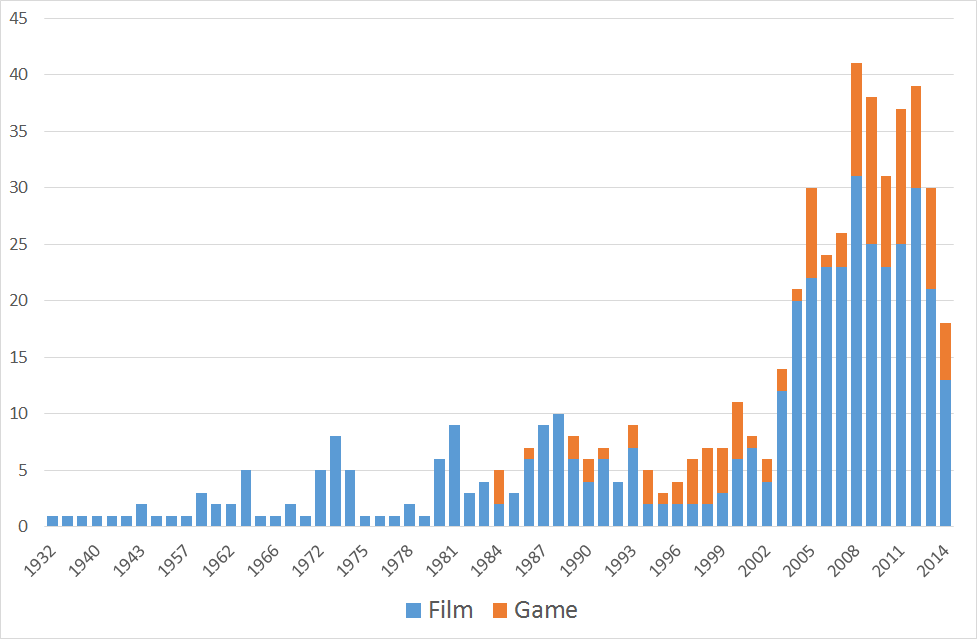

In the years since George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), the number of films and video games that feature zombies in one form or another has increased in a way that suggests something has been touched in the collective unconscious.

While certainly not the first film to feature the shuffling horrors, Night of the Living Dead was perhaps the first to capture the popular imagination, hinting at a social commentary of the Vietnam War and of racism in America. In the chart above I have brought together Wikipedia’s lists of zombie-themed films and video games, including the television episodes of The Walking Dead to date (2014 is incomplete).

One might have expected to see zombies make an appearance in the eighties, the time of the Thatcher/Reagan axis. But the scale of the infestation twenty years later is surely not accidental, as the consequence of their policies wreaks havoc across the world. We are fascinated with our power, appalled and awed at our ability to destroy without remorse, sickened with our own unconscious mania. Fundamentalism can never be far from our minds, whether of the East or West, whether of the vile massacre of schoolchildren in Peshawar by the Taliban or the institutionalised shooting of black people by the police in America.

In the narrative of The Walking Dead, there is a significant issue (massive spoiler ahead), the philosophical implications of which seem to have gone largely unexplored. The infection (cause unknown, but initially believed to be communicated by being bitten by a zombie) is, in fact, present in the living, so all those who die become reanimated. This is hugely suggestive of the concept of Original Sin. Much of the zombie oeuvre can be seen as the visitation of a biblical plague on to the sinning masses (the word ‘plague’ is used often in the series). This underpins the tension between pragmatism and idealism. In another sense, the knowledge of infection keeps the living and the undead connected – all opposites need to be similar so that they can be compared.

Religious anxiety also hides within the explicit narrative (none too well). In the second season, the Christian farmer Hershel tells Rick, our heroic ego, that the plague is a ‘correction’, but attributes it to nature, unwilling to task his god with responsibility. He keeps his undead family members and erstwhile employees in a hay barn, triggering a particularly violent denouement in which Shane (apparently Rick’s shadow self) opens the barn door and, with assistance, destroys the emerging zombies in a hail of gunfire. The last zombie to emerge is Sophia, the girl who the group has been trying to find in the forest for almost the entire season, suggesting that corrupted innocence has been in their hearts all along, just as the infection has been in their living bodies.

Sophia is the ‘Light of God’ of Gnosticism, the final phase of Jung’s anima development, the name that means Wisdom. I wonder if this is unconscious synchronicity or deliberate choice. The zombies, particularly the undead children, represent our fear of the devil, the resurrection of the dead as damnation, hell on earth, the apocalypse, in the form of Satan’s daemons. As Hillman remarks, Christianity removed the depth of the Underworld from our psyche, and the possibility of descent and return. Is the character going down alone to the cellar (or the prison basement in this case) a faint remnant of this?

Zombies invariably look diseased and rotten. Limbs can be wrenched from the undead (otherwise shown as very strong) with mystifying ease. Penetration of zombies with bullets or melee weapons results in a fragmentation of flesh and bone that is invariably accompanied with a vile spurt of dark ichor. In particular, we note that the only way to end a zombie’s undead existence is by destroying the brain. Zombies are shot in the head with bullets, bolts and arrows. They are impaled through eye sockets with steel pipes; skewered with knives and swords, up into the throat and through the soft palate. Zombies on the ground have their heads stomped in violent outbursts of disgust, hatred and grief.

The rotten flesh of zombies is reviled: a lucky living human who has been bitten may have the infected limb severed so as to prevent ‘turning’. Other humans regularly fight with each other, suffering physical trauma, bruising and wounding, even if they are not killed outright. The flesh of the living is almost as tormented as that of the undead. Surely this says more than just a love of the ‘gross’, more than a schoolboy’s delighted disgust at the cartoon popping of an eyeball? For me, it represents a hatred of the flesh that is fully consistent with the idea of a corrupt resurrection, the acknowledgement that (as Jung suggested) resurrection is a fantasy, a defence against death. But this is confused with the idea in Christianity of the corruption of the flesh, the blood that is left behind as we resurrect, and that souls become spirit.

Additionally, there is the destruction of the brain, the part of us confused with thinking, as if we think only with our brains, not our hearts or stomachs. Does this sublime organ have to carry the can for all our mistakes? Psychotherapy insists that we feel everything, placing our sensory perceptions into opposition with our thinking. If we think at all it is supposed to be with our Right Brain, not the sinister Leftie (another opposition and a false one at that, as neuroscience has emphatically proven). Therapists are often trained like this, in the good-natured but mistaken belief that if only their ‘clients’ stopped thinking then everything would be well with them. Some therapists work with Mind/Body/Spirit, and despite a possible fantasy of holism, this feels more like dancing.

There is another very important piece of evidence. Here’s author Robert Kirkman talking to Entertainment Weekly about the absence of a sex scene: “That’s more of a comment on America as a whole and television’s standards and practices than it is on us. It is kind of absurd that in an episode where you see the inside of a bloated, water-logged corpse, you can’t see so much as a butt cheek. That’s the world we’re living in.” This show, that so revels in the realistic depiction of blood and viscera, can only imply human sexual relationships.

Perhaps America fears that sex in the apocalypse would be so primal, so aggressive, that we would see something too uncomfortable for us to bear. We can cheerfully witness the dismemberment of our shadow selves, the rapacious zombie hordes, but we might faint at the first sniff of our own musky animal sexuality. This is surely a reflection on the spiritual transformation so dear to the fundamentalist West. We want to change so badly – it makes us hate the earth. We despise the fleshy and ‘corruptible’: Not so long ago these are things that would be celebrated, not abhorred.

This is where we find ourselves in the twenty-first century. Our comforts are temporary and often delusional, moments of respite in the bleak struggle for survival. Must we destroy the brains of the zombies – the bankers, politicians and oligarchs – when they pose a threat? Or are we too busy fighting each other? It’s just TV you say. Look again at the chart, and perhaps watch the series. Sitting in a café the other day I overheard two women in earnest conversation. One was telling the other about her business selling ‘critical and strategic thinking skills’. She mentioned a colleague, saying, “Her cognitive processing is somewhat impaired… she is very controlling of her environment.”

We are all in Rick’s crew now, bunkered in our prison anticipating nothing better than either the next attack of the zombies, or the wrath of the ‘Governor’. We live in a superficially ordered community that is ruled by fear. It is a society without imagination, without choice. I would like to believe that through ritual and a new pantheism we will find better ways to hold our need for control and power. Will we eventually see through our need to consume at all costs? Perhaps it is too late.

And we danced, on the brink of an unknown future, to an echo from a vanished past.

John Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids

If you have enjoyed this article then please consider sending me a donation to help with hosting costs.