Boris Johnson, COVID-19 and Oedipus Rex – part 1

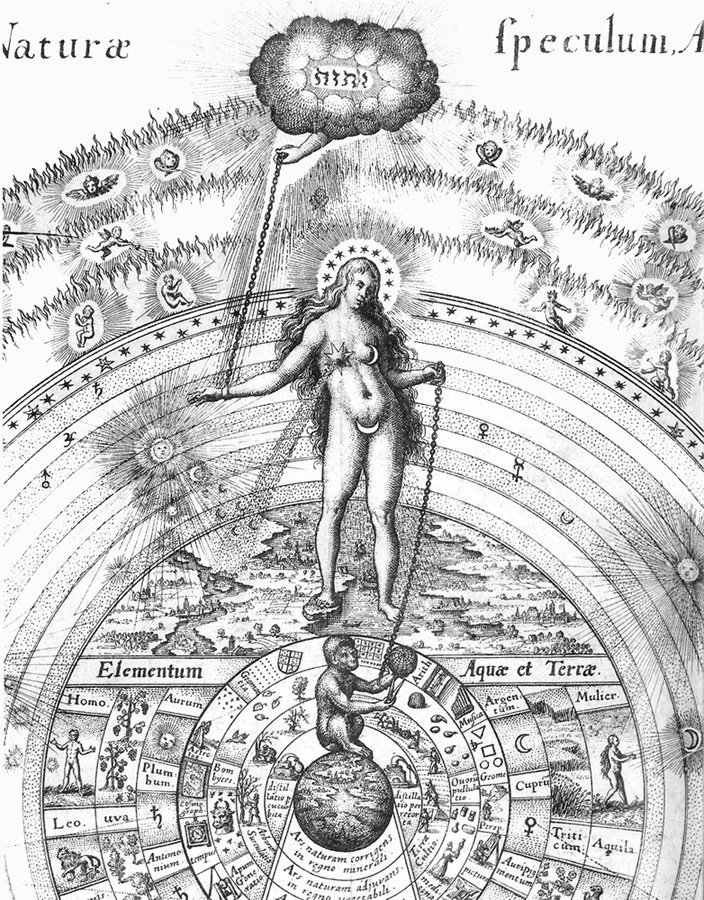

In which I show how the blindness of Oedipus Rex, far from belonging only to ancient Greek myth, continues to be played out in political theatre and personal dynamics, particularly in the person of Boris Johnson. I also show how the response of the state to sickness has not moved on from the Thebes of two and a half thousand years ago, and that the advent of the Coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19) has been managed with a lack of imagination rooted in literalism.

In 1987 James Hillman delivered his lecture ‘Oedipus Revisited’ to the Eranos Conference “Crossroads” at Ascona, Switzerland. Beginning his talk, Hillman identified Freud’s analysis of Oedipus as the defining myth of modern psychology. For as much as Freud understood how myth permeates ordinary family life, he was unable to see how he literalised his own analytical method – his fantasy. Hillman’s address is perhaps the most important critique of psychological method yet made, and it should be required reading in every college of psychotherapy – but it is not, which is a tragic illustration of how the power of myth becomes literalised once it is bonded with money.

Individual patients struggling with self-knowledge are so convinced by the fictions of childhood because they are Oedipus, who finds who he is by finding out about his infancy, its wounds and abandonment. The entire massive apparatus of counselling, social work, developmental psychology – therapy in every form – continues rehearsing the myth, practising the play it practices.

Oedipus Revisited. Mythic Figures. James Hillman Uniform Edition. Spring publications, 2007

We tend to associate the name Oedipus with Freud’s famous complex of that name, but the original story of Sophocle’s play Oedipus Tyrannus (more commonly known as Oedipus Rex ) is the tragedy of a man who takes things literally. In the green boxes I present the story of Oedipus in mini-chapters:

Laius, a prince of the city of Thebes, is forced to leave the city and is taken in by King Pelops. The king has a beautiful son, Chrysippus, who Laius tutors, then abducts and rapes. Returning to Thebes, Laius takes the throne and marries Jocasta. Cursed for this betrayal, and unable to give Jocasta a child, he makes several visits to the oracle of the god Apollo at Delphi and hears that he must sire no male children. Depending on the version, the consequence of having a son would be either the destruction of Thebes or that the son would kill Laius and marry Jocasta.

So far two significant things, two tragedies, have come about. The first is that Laius’s lust for Chrysippus became literal, ruining any relationship Laius might have had with the boy, and breaking the bond of trust he had with the boy’s father, Pelops. James Hillman says this:

Fathers neglect their sons, do not fulfil the erotic bond, because of the incest taboo. Fathers like Laius hear the taboo only literally and so may love only other men’s sons… If Laius is cursed for pederasty, his abducting Chrysippus from Pelops, this pederasty results from his literalism. He hears the prohibition against incest as a prohibition against eros.1 The repressed returns as homoeros.

ibid.

The second tragedy is that Laius literalises the words of the oracle. Heraclitus wrote: “The lord whose oracle is that at Delphi neither speaks nor conceals, but indicates.” Rather than taking the risk that he would not be actually killed by his son, but perhaps humbled or bettered in some way, Laius immediately assumes a literal death.

Apollo is the god of judgment from afar. He is the giver of laws, but he is also called Far-darter, as his arrows bring remote vengeance. Nowadays, assassination by drone belongs to his archetype. He is associated with Helios the sun, bringing light to the darkness. He can deliver people from the plague, or he can inflict it. He is associated with medicine, either by himself or through his son Asclepius. He inspires: we say, “it came to me like a bolt out of the blue.” But we need to be careful with the sudden answer, the miraculous insight – the suddenness of it can be a trap for the intellectually arrogant.

Let’s move on to the next event:

Drunk, and unable to control himself, Laius has sex with Jocasta. Nine months later she gives birth to a son. Still literalising the words of the oracle, Laius has the baby boy’s feet pinned and orders Jocasta to kill the child. Unable to comply, Jocasta sends the infant away with a servant who intends to abandon him on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron, but who instead gives him the baby to a shepherd, who calls him ‘Oedipus’, which means ‘swollen foot’, and this shepherd delivers him to the childless couple King Polybus and Queen Merope of Corinth.

Laius, who loved a boy, tries to kill his own boy. The mountain has a history itself, it is a place bewitched, a place of death and madness, a hard place. But for the ancient Greeks a riddle (ainigma) has a second, hidden meaning. In the play, the Chorus refers to the mountain as Oedipus’ “nurse and mother”. Following Hillman, we can also see that there is:

… an archetypal necessity for a father to ‘isolate, neglect, abandon, expose, disavow, devour, enslave, sell, maim, betray the son – motives we find in Biblical and Hellenic myths as well as folklore, fairy tales, and cultural history.

ibid.

Nowadays it is customary to lay much of the blame for our woes at the feet of our parents. We hear a lot about abusive fathers and neglectful mothers. We carry an idealised sense of who our parents were or should have been. Hillman points out that whenever we idealise a parent we stay stuck in false security, that we are bound to the imagined ‘good model’ of a parent, teacher, guru, boss, therapist, that we imitate. But when the idealised image is crushed, when we lose both the model and the power. Then, and only then, can we enter initiation.

Naked, toothless, bleeding, in pain, alone, unequal to the task and in need of elders, feeling terrifyingly young – these are the initiatory experiences. They shatter the icons of remembrance, and devotions provide no protection… we are moved from having to being, and in Jung’s [term], “being in soul”, esse in anima.

ibid.

It is notable that Boris Johnson seems to have an idealised view of his cantankerous and reactionary old dad, but has allegedly abandoned or neglected any number of his own offspring. In the affair of Dominic Cummings, something mythical is playing out as well. Cummings excuse for breaking the conditions of the Coronavirus lockdown (breaking the bond of trust) is a sick son. At the time of writing, he still has the support of Johnson (and who knows which of them is the ‘father’ in that relationship) but one or both of them might yet be abandoned on Cithaeron for wild animals. Already you can hear the hungry howls…

By pointing out the archetypal nature of abandonment and abuse, I want to make it clear that I do not condone it. But we must see that myth and fairy tales are replete with murderous and evil parents, guardians, kings or queens. The stories explain that Initiation can take us to a place where we behave differently – the alternative is to be blind to it, staying a perpetual victim, longing for an illusory corrective experience. We demand it from partners and divorce them when they don’t come up to the projected expectation. We want it from a therapist, then leave when it’s not given. We stay in a state of perpetual disappointment rather than benefiting from a valuable counter-education. If only the education we get at school could teach us about this hidden gift instead of the irrelevant pseudo-science of economics.

Time passes, and the adult Oedipus hears a rumour that he may not be the son of Polybus and Merope as he had believed. He goes to the oracle, determined to discover the truth, but all he hears is that he is destined to marry his mother and kill his father. Appalled at the possibility of this happening, Oedipus leaves Corinth. He travels to Thebes, but on the journey he comes to a crossroads where he contests right of way with another charioteer and kills both the charioteer and his passenger, an old man who, unknown to Oedipus, is actually his father Laius.

This is the next terrible tragedy. Rather than reflect on the oracle’s indication, discuss it or take counsel, Oedipus is seen to be as literal as his real father. The first part of the prophecy is enacted – literally. The word ‘crossroads’ in the play does not refer to the meeting of two roads giving four directions, but rather a place where three roads meet. The Greek traveller Pausanias warned other travellers of the danger of malevolent nymphs, particularly strong at noon (and Cithaeron was a place said to be home to nymphs who would drive men mad), saying that gifts should be placed where three roads meet: gifts of milk, honey and eggs. There is softness in this gift, respect of place, and of crossings, which Oedipus, who takes the words of Apollo literally, cannot observe.

Arriving at Thebes, Oedipus encounters the Sphinx, a monster that asks travellers a riddle and devours them when they offer the wrong answer. Oedipus answers correctly and the Sphinx throws herself into the sea. Oedipus enters the city a hero and is rewarded with the kingship of the city and the hand of the newly widowed Jocasta as his bride.

Oedipus the hero takes on the Sphinx, the monster that poses passers-by an ainigma and devours them when they answer incorrectly. The idea that the riddle posed was the one that goes, “Which creature has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?” was apparently added to the myth later. The enigma may have been the Sphinx herself, but heroes rarely look for second or hidden meanings, preferring to deal directly with the obvious. Heroes also have a tendency to slay animals, pitting themselves against the earth, and they inevitably suffer greatly for it. The symbolist painters Gustave Moreau and Fernand Khnopff seem to have understood the myth far better than Oedipus, presenting us with danger, but also with a quality of shimmering seductiveness.

Boris Johnson, first as Mayor of London, then as Prime Minister, is our modern-day Oedipus. His public school education even enables him to parrot Ancient Greek, a party trick to amuse and impress the less privileged. Johnson has his Sphinx as well, in the shape of the EU, an animal also made up of many disparate parts. Johnson and his masters first carefully influenced the people, convincing them that the EU was a more dangerous beast than they had realised. Then, (like Oedipus, he was either unprepared or unable to ask the Sphinx what it was) Johnson merely repeated the mantra “Get Brexit Done” many times, and this simple spell convinced the people that the EU was every bit as monstrous as they had been led to believe.

Entering parliament,2Johnson the ‘hero’ doubtless looked forward to five years of personal wealth creation while going through the motions of leadership, shouting down the opposition at the despatch box with all the punchy bluster of the playground bully, and giggling with his posh cronies. Unfortunately for him, both the city and the rest of the world became physically sick, a powerful indicator of other diseases, hidden but very real: the sickness in our depleted soil, our vanishing water and our toxic air.

A pestilence strikes Thebes, and the people go to Oedipus, begging him to help. He refers to the people as ‘children’, telling them that he has sent his brother-in-law Creon to the oracle of the lord Apollo at Delphi. Creon returns, telling Oedipus that to be rid of the plague, Oedipus must bring those who murdered Laius to justice.

Oedipus, ignorant of the truth, summons the blind seer Teiresias, who knows the answer but refuses to speak. Oedipus becomes enraged, accusing Teiresias of complicity in the killing. Teiresias becomes incensed, finally telling Oedipus that he is the murderer. Oedipus, suspecting a palace plot orchestrated by Creon, abuses Teiresias, mocking the seer’s blindness, to which Teiresias retorts that it is not he who is blind but Oedipus.

Oedipus, full of fury, summons Creon, accuses him of being the murderer and demands his execution.

Hillman pauses at this point, and asks these questions: ‘How does a city act when it is sick? What moves do its rulers make? What notions of remedy arise from the sick city?’ Let us look at each of the actions that Hillman identified in the play and relate them to the Coronavirus crisis with the help of our friends of the fourth estate

| Action in the play | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| The sick city calls upon the leader to find a remedy | A single solution to a complex problem |

| The leader calls upon Apollo to reveal the cause and the cure | The government turns to diagnosis and correction |

| The sick city summons the shaman, seer, or prophet | Reliance on prophecy |

| The city purges | Language of pollution and expulsion |

| The city makes edicts | Scapegoating, forbiddable persons, commands |

The sick city calls upon the leader to find a remedy (a single solution to a complex problem)

A priest of Zeus brings public concern over the plague ravaging Thebes to Oedipus the King. Our own beloved media takes a similar approach to the citizenry of Thebes. It does not matter if the media tone is wheedling, beseeching, critical or disdainful, it amounts to the same thing. An approach is made to a leader, and that leader will live or die by the actions he or she then takes. In the examples shown, the right-wing newspapers try to elevate Boris Johnson to a mythical level, presumably in furtherance of their owners’ political aims. The people are ‘children’, only capable of breaking rules never making them. In Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon is complimented on her leadership much as a patronising grandparent might observe that so-and-so is such a good little mother.

In contrast to Oedipus’ Apollonic monotheism, the Chorus invokes not just Apollo, but Zeus, Artemis, Athene and Dionysus.

Bacchus [Dionysus] to whom thy Maenads Evoe shout;

Oedipus Tyrannus. Sophocles (tr. F. Storr 1912) – http://www.ancient-mythology.com/greek/oedipus_rex.php

Come with thy bright torch, rout,

Blithe god whom we adore,

The god whom gods abhor.

Sophocles clearly wants to warn the audience of the danger of not just a stuck position, but an Apollonic one at that. Oedipus’ figurative blindness comes about because of his fixity, his inability to see beyond analysis and dogma. When it is too late and the tragedy has played out and Oedipus has blinded himself, he also finally understands what has happened:

CHORUS

ibid.

O doer of dread deeds, how couldst thou mar

Thy vision thus? What demon goaded thee?

OEDIPUS

Apollo, friend, Apollo, he it was

That brought these ills to pass;

But the right hand that dealt the blow

Was mine, none other. How,

How, could I longer see when sight

Brought no delight?

CHORUS

Alas! ’tis as thou sayest.

The leader calls upon Apollo to reveal the cause and the cure (the government turns to diagnosis and correction)

Oedipus sends his brother-in-law Creon (the brother of Oedipus’s wife, Jocasta, who – unbeknown to him – is actually Oedipus’s own mother) to Apollo’s oracle at Delphi to ask what is causing the plague and how it might be removed.

The modern equivalent to visiting the oracle is a consultation with experts. In our case, the experts have been the government’s chief medical adviser Chris Whitty (and his deputies) and the government’s Chief Scientific Adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance. Chris Whitty and his deputies have all been called upon to resign for one reason or another, often by competing experts. Before Vallance took the government position he spent 12 years working at GlaxoSmithKline, finishing as Head of Research and Development.3 Coincidentally, In 2012 GSK was fined $3bn for fraud in the US, and in 2016 £37.6m for bribery in the UK. By way of further coincidence, GSK’s manufacturing and research base is located in Barnard Castle, County Durham, to which the Prime Minister’s Senior Adviser Dominic Cummings drove in order to ‘test his eyesight’ before returning to London ‘to get vaccine deals through’. On the day of Cumming’s return, GSK announced an agreement to develop a COVID-19 vaccine.4 Obviously all these events are entirely unrelated.

Throughout the pandemic, the government has assured us children that it had been ‘following the science’, yet the scientists who make their views public in social media seem to be almost unanimous in their condemnation of this. The science itself has been damaged first by underfunding, then by the creeping commercialisation of laboratories. If we have faith in the science, then we place it on a pedestal from which it will quickly be toppled. The ideology behind the dithering and the lies is profit. We know that the 1922 committee of the Conservative Party (always referred to as the ‘influential 1922 committee’ by the media) has been highly impatient of the Coronavirus lockdown, maintaining that thousands of businesses will go to the wall unless they are allowed to trade normally (translation: the members of the committee and their friends will lose money). The billionaire media owners sense the need to crush any optimistic feeling that life might be different, so even while we are still in the middle of the pandemic we are being warned that our punishment for being furloughed or otherwise incapable of propping up the rotten corpse of capitalism is greater austerity.

The word ‘hope’ appears often in the newspapers. Hope is what children do at Christmas and birthdays, or what we might do if we’re planning a trip to the beach. To ‘hope’ for a vaccine is meaningless: has it been tested? How has it been tested and for how long? Should we ‘hope’ that it has been tested adequately, or ‘hope’ that it is safe for kids to go back to school? The words of the headlines make children of the readers, who will be diagnosed and corrected. Lest we forget, this has also been a pernicious trend in psychology – even in the growth of such apparently harmless techniques as ‘mindfulness’. Developmental psychology, neuroscience and ‘mindfulness’ all seek to take a symptom, give it a name and then correct it (panic – social anxiety disorder – attend ‘mindfulness in nature’ classes) so that the patient can get back to work. No matter that the cause of the symptom is still the same, you can deal with it by taking a walk in a landscape that is disintegrating before your very eyes because it is held in contempt.

This blindness, which manifests particularly as faith or belief in facts and diagnosis, leads us ever further into literalised myth. It makes the path between the virus and what happens afterwards not so much linear but circular – those with the power will try to hang on to that power at all cost.

The sick city summons the shaman, seer, or prophet (reliance on prophecy)

Teiresias the blind seer is the prophet who Oedipus summons, much as Boris Johnson has summoned not just Chris Whitty and Patrick Vallance, but the dark figure of Dominic Cummings, the man whose powers stem from an uncanny ability to read the public mood – at least until he broke his bond with the public. But Teiresias can see, even though he is blind. He knows that Oedipus is following a tragic path by looking for the murderer of Laius, just as Johnson is following a tragic path by placing ideology and politics over the safety of thousands of people.

Where Oedipus attacked Teiresias for not speaking, it seems likely that Johnson gagged his prophets, frightened that their messages of doom would cause further damage to the precarious economy that he finds himself in charge of. Instead, he used a standard tactic of politicians everywhere, he produced an elderly person of State, the Queen, to deliver a Message to the People. Johnson hoped that a message from the Queen would appeal to his core voters, but even that seems insufficient as his base begins to crumble.

‘Track-and-trace’ is another modern oracle, one which Johnson claims to be ‘up and running’ but which is hopelessly flawed. It is the product, like so much else in this tragedy, of spin.

The city purges (the language of pollution and expulsion)

Pollution and expulsion have been a part of our shameful national discourse for a long time, and here I do not refer to the pollution of the environment but rather the knee-jerk response of the people, betrayed by the experiment of capitalism. Feeling intuitively that plague was in the land, well before the physical manifestation of COVID-19, the majority of voters supported Boris Johnson – the ‘hero’ who promised to slay the EU, to expel foreigners, and to bring the land into the sun of Apollo. Previously, the voters of the United States had done exactly the same when they entrusted Donald Trump to ‘clear the swamp’. The tragedy of late capitalism is that people confuse heroes (a difficult enough breed at the best of times) with titans. The media, as quick as politicians to reverse position when deemed prudent, saluted ‘our NHS heroes’ and encouraged the shaming of those who refused to go along with this hypocrisy by clapping in the streets.

Special mention must go to the Daily Star which has a particular penchant for alarming stories featuring wildlife. Read the headlined article and you will find that the reason for the ‘psycho’ seagulls and booming rat populations can be squarely laid at our own doors, but the headlines pretend otherwise. The Daily Star is merely the explicit face of the general antipathy the culture has towards nature, a direct consequence of belief in transcendence and Cartesian dualism. Nature is liked only when it is ‘cute’ or under control.

The city makes edicts (scapegoating, forbiddable persons, commands)

At any time of crisis, the media, supported by many of the people, look to scapegoat. Johnson, medically obese himself until he became ill with COVID-19, is now using scientific evidence that people with obesity are more vulnerable to the virus. Obese people often have psychological difficulties (it is often a consequence of childhood sexual abuse) and are most often found at the bottom of the socio-economic heap. It is entirely invidious for Johnson, or anyone else, to attack the most vulnerable parts of society. It is Johnson himself who has the power to save the NHS, by delivering proper funding and decent rates of pay, rather than operating a sleazy bust-out that will deliver the carcass of the service to his disaster capitalist cronies.

But the media loves the scent of blood, and where rules are being broken by people in the public eye, the media will take great satisfaction in telling us, regardless of what hypocrisy that might involve. To suggest that Cummings ‘must fall on sword’ (rather than ‘resign’, ‘leave’ or ‘go’) also shows us that the mythical is at work.

Jocasta enters and tries to calm Oedipus with the story of how Laius had heard a prophecy at the oracle telling him that he would be killed by his own son, but (as everyone knew) Laius had been murdered by bandits at the crossroads. Oedipus becomes nervous, anticipating the truth. A messenger brings the news that King Polybus has died, and Oedipus feels temporary relief but is still concerned that he might commit incest with his mother. The messenger tells Oedipus not to be concerned because Merope is not Oedipus’ birth mother. The messenger knows this because he had been the shepherd who took the baby Oedipus from Jocasta’s servant.

Oedipus, suspecting now what has happened, asks the whereabouts of Jocasta’s servant. By a further cruel turn of fate, it is revealed that this servant was the only surviving witness of the events at the crossroads. Jocasta, knowing the truth herself now, pleads with Oedipus not to pursue his investigation further. He refuses and Jocasta runs into the palace.

The servant is found and, under threat of torture and death, he reveals the truth to Oedipus. Meanwhile, Jocasta has hanged herself in the palace. Oedipus calls madly for a sword, shouting that he will cut out her womb. Entering the palace he finds Jocasta hanged, and in a fit of grief and remorse takes a pin from her gown and puts out his own eyes.

Oedipus is literal to the end, poking out his own eyes when he finally sees the truth. These are Sophocles’ messages, speaking clearly to us from the distant past: first, you are only a victim of fate if you take it literally. Second, once you adopt a fixed position or ideology you are doomed. Third, if enough people tell you the same thing it is wise to listen. Fourth, sometimes rooting around in the past is a very bad idea. All of these things apply to the world of counselling and psychotherapy, but they also apply to the world. Sophocles asks us to understand how even the best of leaders can be blind to the truth until it is too late. Unfortunately for our modern selves, we have chosen monsters for our leaders.

Oedipus begs Creon to be exiled, but Creon says that the oracles must be consulted first. Oedipus asks Creon to look after his two daughters/half-sisters, Antigone and Ismene.

The play ends. Much later in his life, Sophocles wrote ‘Oedipus at Colonus’, and that is the text that will concern us in part 2.

After COVID-19, nothing can be the same again. But capitalism is deeply entrenched. Shopping is addictive, the first IKEA stores to re-open attracted thousands prepared to stand hours in a queue to buy cheap unattractive furniture. Our culture is fuelled by compulsive behaviour. It is clear to many that the next virus only has to be fractionally more potent than COVID-19, and the infrastructure of the world, this fragile edifice of toxic financial instruments, will collapse. There will be mass hysteria, looting and violence on a scale never before seen. The state has an opportunity now to take action, but it will take decisive cross-party leadership for that to happen, and I fear that there are no politicians of substance left. One might imagine that Boris Johnson’s brush with death might have opened his eyes, but he seems as hollow as before, whereas the sightless Oedipus managed to change what needed to change, as we will see in Part 2.