Boris Johnson, COVID-19 and Oedipus Rex – part 1

The 2,500-year-old tragedy of Oedipus continues to be played out: Boris Johnson’s literal and unimaginative response to COVID-19 has not moved on.

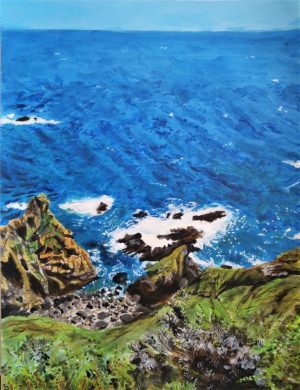

You can see my first two posts on Autumn here and here. As before I have added spreads from the Ladybird book ‘What to look for in Autumn’, written by E. L. Grant Watson and with illustrations by C. F. Tunnicliffe (copyright acknowledged). The focus here is on the inedible (by humans) that comprises the bulk of the harvest.

Previously I said that the work has its own narrative because the posts explore change in the British landscape over the last fifty years. We see some successful species, ones that have managed to withstand the difficulties caused by population and agribusiness. There are many others that have been less fortunate. I hope that the skein of life, the web that connects us as humans and the other than human, becomes apparent as the series continues.

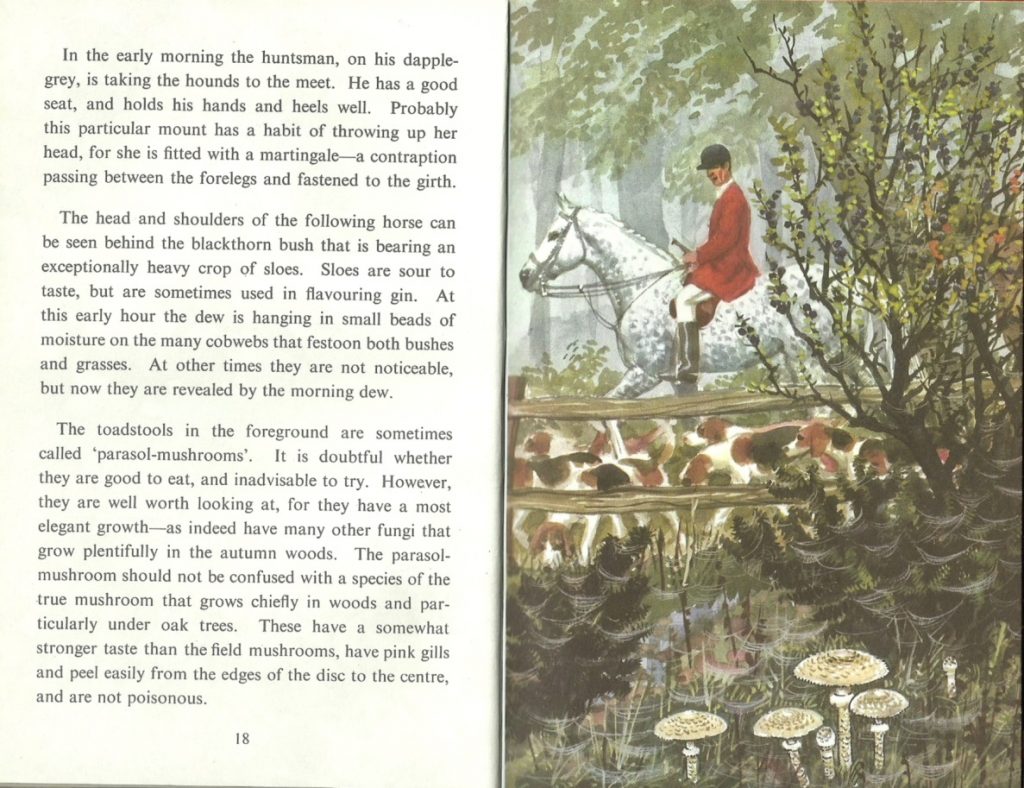

Fox hunting may seem to have had its day but it is still legal in Ireland. A powerful lobby exists to bring it back. The lobby is led by the members of the House of Lords (who refused to pass the legislature) and the Countryside Alliance. But hunters no longer have an affinity with the land. The majority of foxes still killed are the victims of illegal hunts and poachers.

I cannot see that a pack of dogs, followed by a body of people on horseback, who in their turn are followed by still more people on foot and in cars, is anything other than a gross travesty of hunting in any form. It is neither ritual (because it has no spiritual significance) nor is it a sport. The prey is uneatable, as Oscar Wilde so memorably pointed out. So the hunt continues, sans fox, as a relic of privilege. The hunt itself is a dominant hierarchical symbol that is a mirror to the worst excesses of capitalism. It serves to illustrate the contempt that those who are elevated (whether on horseback or in power) have towards those without status.

.Quietly framing the anachronism of the hunt are the wild plums we call blackthorn (Prunus spinosa). The acrid fruits are called sloes. They are also inedible but a fine flavouring, particularly for gin. There is a fine crop of Parasols, probably Macrolepiota procera. The author doubts that they are edible. In fact, Parasols are delicious, though they need to be positive identification before eating, and may not be picked from nature reserves.

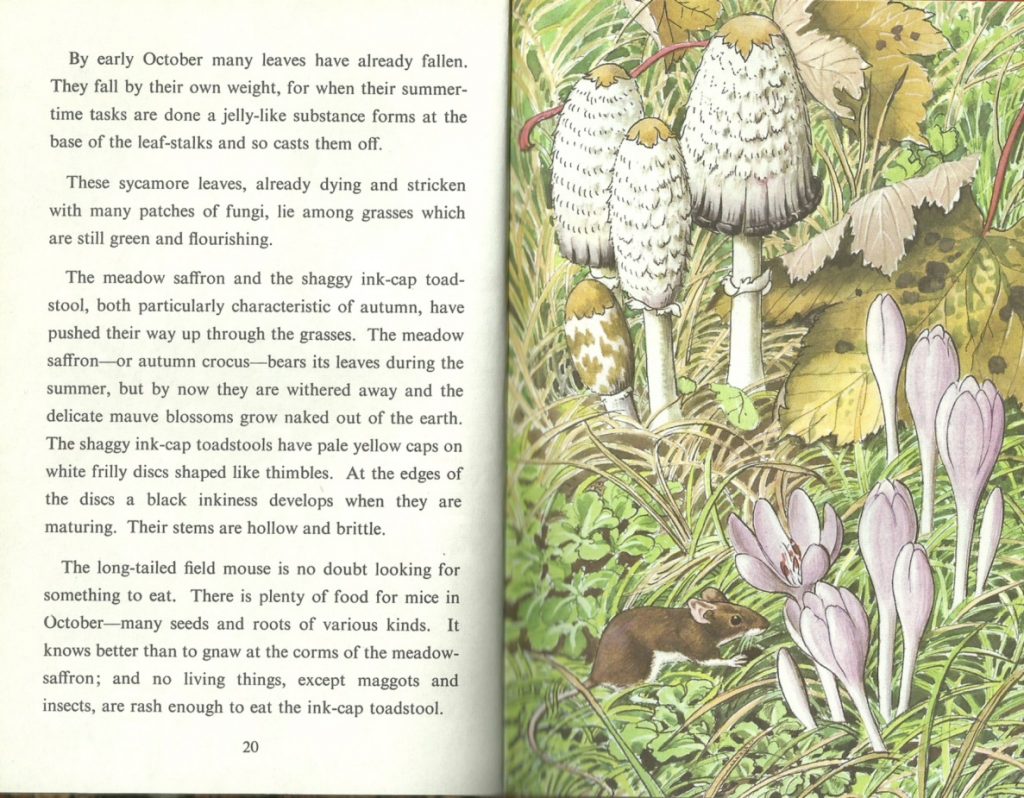

The distrust of fungi in these islands so prevalent fifty years ago makes itself known again on the very next page. The author correctly asserts the toxicity of the Autumn Crocus (Colchicum autumnale) but goes on to claim that ‘no living things’ except maggots and insects, would touch the ink-cap toadstool. In fact, the Shaggy Inkcap (Coprinus comatus) is also delicious when young.

We have to be careful about looking at the past romantically. Some loss is welcome, and one such practice was the back-breaking work of picking potatoes by hand. E.L. Grant Wilson wonders if the tubers of Black Bryony (Dioscorea or Tamus communis) might be edible. Don’t be tempted, they are not. This is another plant that has suffered from the grubbing up of hedgerows. I used to regularly walk a path that had Black Bryony growing on one side and White Bryony on the other. The two plants are not related. Black Bryony is our one representative of the Yam family, whereas White Bryony belongs to the cucumber family. The fruits of both are inedible.

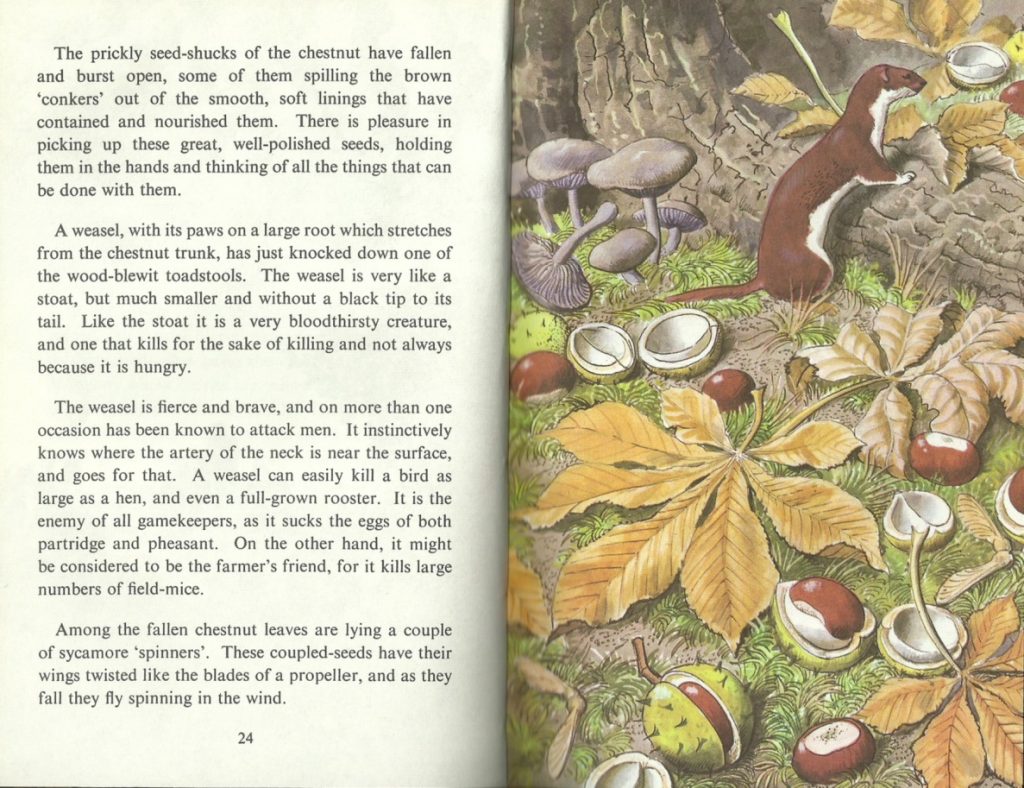

The Wood Blewit (Lepista nuda) is not perhaps a species to seek out for the table as it seems to disagree with some people. The naturally drying fallen Horse-chestnut leaves shown here are now only seen rarely because of the Horse-chestnut Leaf Miner (Cameraria ohridella). The predations of this leaf-mining moth prematurely dry and shrivel the leaves. Imported plants have enabled the moth to spread from its home in Macedonia. Since the late 1970s, it has moved inexorably northward. The tree is left unharmed, it seems, but this new moth species is also seen as a consequence of the reduction in diversity caused by over-planting. The tree is only distantly related to the Sweet Chestnut. The seeds are inedible, even to horses!

The Weasel – here the Least Weasel (Mustela nivalis) is shown – has a good population and is not of concern. It also has a fascinating mythology, presumably owing to its shrill calls and its fierce demeanour. The evidence for a weasel killing ‘for the sake of killing’ seems to come from owners of livestock, chickens, rabbits. The oncentration of animals in a small space creates confusion. I can’t see that one can apply a moral judgement to a weasel, and I wonder if this comes from the Puritan notion that weasels were the familiars of witches. The name itself has a base meaning of ‘stinking animal’, from its musky scent, and the connotation of ‘weasel’ as something underhand (‘weasel words’) is related to the weasel’s ability to suck out the contents of an egg without destroying the shell.

Teal, Shovelers and Goldeneye all share RSPB amber status as, alarmingly, does the black-headed gull. The lapwing has red status, with a very much reduced population. It was wonderful to see them at the London Wetlands Centre, of all places. Of all these lakeside birds then, only the Heron enjoys a stable population, but it is a comfort to know that they are still all with us, decorating the still waters of late Autumn and Winter.

If you have enjoyed this article then please consider sending me a donation to help with hosting costs.